John Hoyland: Today’s Turner

Studio Visit

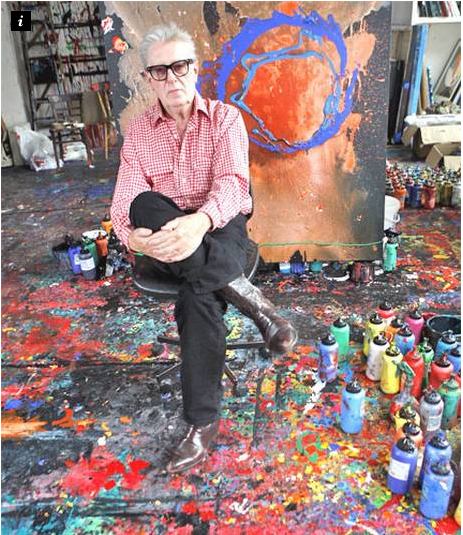

It seems the most appropriate time for me to visit John Hoyland’s studio. As a painter having filtered down the importance of what a painting should be about, I needed to know from somebody who had been looking for a lot longer than me, and from what I sensed in somewhat similar fashion. To Hoyland his paintings: “…….are an equivalent of nature, not an illustration of the latter…..” (John Hoyland Moorhouse RCA 2000 p 14). And to Hoyland nature includes all. During my visit to his studio with one of his new paintings, titled, ‘Mind Horizon’, I asked Mr. Hoyland as to what his next new paintings would be like, and he said he was not sure, about anything. Hoyland has always been about something mystical. The spaces he creates are meant to show the viewer what one cannot yet see. Not pictures of nature as you see it, but yet another: isn’t that what the mystics spend their life doing.

Hoyland grew up in Sheffield. I had not known any of this when I had visited his studio. I remember seeing his work at the Hayward I think it was a few years back, when I was struggling with my own form. I remember thinking that in some of his paintings he had stepped over the edge of the acceptable form in Art. Form that perhaps did not work. They were a series of pink paintings, yet he put them out as his own. Saying, I saw this, it works for me, and if you don’t see it keep looking. I admired the fact that he did put it out as his own. He would have signed it and dated it and it would have meant something to him, and meant to stir the minds of others. You will see it in the history of his works. In some he stepped out of the acceptable and in others he stayed within the realms of what is expected. But then what does form in Art satisfy, but not just the hardwiring that is in our brain. We come with our own idiosyncrasies, which shape us. What we are, both as what we are hardwired, to what we experience in our daily life, which gets colleted as our ‘past’. Hoylands past starts in Sheffield: his parents married early and he grew up as part of a young family. He was born in October 1934 (John Hoyland: Mel Gooding pg 8). The only artistic presence at this stage in Hoylands life was his grandfather who was a Lithographer. His grandfather had left his family and went to America, but Hoyland’s mother was always encouraging in his interests. Hoyland still holds this sense of independence that his grandfather portrayed. At 72, he does not live with his girlfriend of many years but remains in his studio flat on his own. Painting needs a solitary space to function. Was it Peter Cook, actor and comedian who said the best thing for husband and wife is to have 2 separate homes in the same street, each with ones own space. At eleven Hoyland, had already got into the arts by going to the Sheffield School of Arts and Crafts. He progressed to finally concentrate in Fine Arts. ‘In his teens he already had a natural personal reserve, an inner necessity to work things out for himself, and a determination to travel roads of his own choosing’. (Mel Gooding, pg 11). Hence it was in Hoyland’s making from his early days to find and look for his own answers. It would become the centre of his Art.

The only reference that an upcoming artist has are his elder contemporaries. Hoyland’s very early days of looking were inspired by the European artists: Van Gogh, Cezanne or Picasso. His teaches were dismissive of them: ‘They look like French painting, Hoyland! Why try to paint as French.’ The reference point of most artists is normally the, front line of Art, those contemporaries original in their outlook, are setting the trends. But one must remember that all there is are those persons who have for whatever reason of their own have come to the Arts to make objects that have no other value it might seem but to decorate a wall in one’s home. It might seem so that this is it. To the artist it is just another job, or because, ‘one cannot live by bread alone….’. But I am sure all those artists’ who seriously spend all their lives making art have in a sense put forward more than just an object but rather a process of their mind. They do it in a way that is peculiar to them. They observe how their minds turn and how the Self or the Being exists in its space. And through their workings we see our own lives played out and understand it better. Hoyland stuck in Sheffield was determined to get out so he could experience what was outside Sheffield, by seeing the original works and not from books. So when Brian Fielding a senior of Hoylands at Art school had returned from London with a small book on Nicholas de Stael, he must have asked himself ‘what time is the next bus to London’. I am just speculating here as to his excitement at that time. It was with fielding that Hoyland had his most intense and passionate discussions. Though Hoyland was from the lower middle classes of Sheffield, Fielding had gone to Grammar school. If the ‘Truth’ finds its way out through a relationship then both Hoyland and Fielding were gifted to each other. Before Hoyland had made it to London, at Sheffield, he had shown good skill in painting Realistic work. At his studio he had shown me the painting he did of his father, realistically painted, and also other documented work I had seen, such as Still life (1954) and Sheffield (1954) showed that he had skills where he could have painted realistically if he wanted too. But he had said at his studio that there are some artists who paint realistically who do not understand the subjective awareness that is required of an abstract painter. It comes I feel from living in a certain space for long enough until that space then becomes you and you then work from it. John Hoyland I feel not only understood the space he stood in very well but also was not afraid to step out when he thought it was necessary. I see that daringness in his work and he would have done it not because he had too – it would have been safer to stay within the limits – but because it was important to him and to all of us that he took those risks so the possibilities exists to all of us who seriously are also looking. So looking at how now he, sitting in his great studio at 72, when in 1956, at the encouragement of his friends, among them Brian fielding, he found himself at the Royal Academy.

At the RA (Royal Academy) Hoyland had still persisted with the object (still life with fruit and flowers 1957) still looking and finding, but one point was clear, as seen from his early work: that the importance of colour and its juxtaposition to each other to make form will remain with him in his future work. Though unknowingly an artist may pursue his work diligently, exploring, but the gist of his work, his idiosyncrasies will show what his preoccupations will be in the future. Hoyland broke through with his ‘Abstract Composition’ 1958, where the composition was only of colour shapes. Hoyland at this stage of his development was still ‘making’ constructing his paintings rather than finding as his later paintings might have suggested. Hoyland had not long been out of Sheffield. Even tough his foot firmly placed in contemporary Art London, he was still a novice because he was still finding his true self. But even then he liked his colours. His favourite colours were red, orange and green. He read courses of Johannes Itten. Itten had said to his Bauhaus colour course students: ‘If you, unknowing, are able to create masterpieces in colour, then unknowledge is your way. But if you are unable to create masterpieces in colour out of your unknowledge, then you ought to look for knowledge’. (Pg 21/22 John Hoyland, Mel Gooding). Well Hoyland decided to find knowledge. But you can sense that today’s Hoyland has this uncanny way of choosing his colours. With Music one might find geniuses at an early age. Born with a talent that is extraordinary as if bestowed on him in another lifetime. But with painters, you find that they have to find, come to their form with time. Though Hoyland chose to learn his colours, my experience at his studio (2008) I feel that his subjective awareness of his colours and his sense of putting them together somehow does not have the feeling that it is learned. I sense a kind of intangible knowing of colours from his work. His respect for the found mark as given and not made. But I did want to ask him, ‘Do you think yourself into an idea for a painting or does it come to you?’ But I did not. But I think I got the answer from just being there in his studio. He had asked me if I wanted to look at some of his drawings in his sketchbooks. He picked one up and said that all the drawings in the book were done recently. I looked through them and they seem to have been done by colour markers. They were not pencil drawings exploring form, but rather sketch paintings. It is as if he thinks in colours right from the word go. But when I looked at his drawings I noticed that they did not look anything like his paintings. Trying not to be rude I said to myself, I have to ask him. So I did. He said that they got filtered down. I don’t know why but I was just on the verge of shouting ‘bravo!!’ ‘Bravo’ for me and getting an answer I can use. Instead I must have whispered something like, ‘wow’. Hoyland had sensed that the essence of his Art was to show the ‘Truth’ of the process as clearly as possible and the way to do that are to keep it to the minimum. His whole career I feel had been refining this process, filtering it down to capture that thing, that comes across to his viewer, to show him/her that there is something else that exists that you don’t know about and I don’t need to load up my canvas to show it to you. You cannot pass a John Hoyland painting without having to stop and ponder. You want to know where he is at as a person and how did he make the painting happen.

If a painter can start his career back to front then he would have saved himself a lot of time looking before he finds himself. Five years from the end and back he could then stop painting as he would have been at his best and all that he needs to know both tangible and intangible would have been discovered. Impossible right? So Hoyland too had to go through that road of discovery up to the whitechapel show in 1967 and after. He looked like he was looking around him and making paintings. Unlike his later years where he was finding and making. In the year up to 1967 and after he was looking and making. His paintings look constructed thought his preoccupation was still colour shapes finding their places next to each other. You get the impression that the painting was planned and then painted. Unlike at present where his drawings gets filtered down. In his early days there were lots of Rothko in them. At his studio Hoyland had said that he had spent time in New York teaching and at that time he had met Rothko, Barnett Newman, Robert Motherwell, Reinhart etc. But he had not met Pollock. I asked him why did he think that Rothko killed himself. Hoyland said that he had painted himself into a corner. I guess Pollock did that too. Hoyland must have learned from all this, as his worked had always moved. He took risks that Rothko and Pollock did not take. I guess when the money kept Kicheng into Rothko and Pollock’s hands why would one have to take risks. Hoyland was not afraid to step out. He always kept looking I felt; yet in all his work there was always something of John Hoyland in it. The sense of spontaneous activity and yet firmness in decision making in deciding his final composition gives the viewer a sense of the process, stripped clean of all the thinking that would normally cloud a painting.

Robert Motherwell had admired Hoyland’s work. In 1973 he had remarked to Hoyland that he could be the next Turner. There is something very cool and real about this. The way Hoyland moves his colours around his canvas and how he tries to capture the presence of the found image has a strong relation to Turner. But John Hoyland is a modern Turner as he is not dealing with nature as such but equivalents of nature. In his 1979 Serpentine Catalogue you can feel the true nature of his artistic ambition: ‘Paintings are not to be reasoned with, they are not to be understood, they are to be recognised. They are an equivalent to nature, not an illustration of it; their test is in the depth of the artist’s imagination.’ (J. Hoyland: Mel Gooding pg 138.)

Malevich had also said, ‘Things move and are born, and we make newer and newer discoveries.’ (Mel Gooding, pg 138).

When one does not have a reference when painting, and the most important thing is finding what is new, the process can be a complicated one. From not knowing to finding, has to require certain processes of what might look like play with spontaneity and chance initially playing a big part in making of the painting. You will see this in his paintings in the 1970’s. Hoyland went from formal construction, Hoffman like paintings, to play and find in the 70’s. With his play and find paintings you can see that everything goes in application of his paints, until he sees something and then freezes it, like it was made. The paintings during that time did not have titles, but only dated, acrylic on cotton duck. It might seem true to self that a wholly found painting cannot be titled. One such painting sits in Hoylands flat today. He said that Patrick Caufield liked looking at that painting every time he visited. Today’s contemporaries including Mick Moon are all friends. Today as before, visiting and reminiscing and discussing. They have in the last 50 years contributed and shaped the British art scene.

I had asked Hoyland, perhaps daringly, that at 72 why did he still had to paint. He said that he just had to. ‘Hoyland had suffered no doubts about his vocation: he paints because that is his chosen means to the poetic expression of a life (J. Hoyland: Mel Gooding pg 157). In an age when conceptual art rules, and the validity of painting being questioned in a more modern context, and where commercially technically constructed figurative art is still cool, John Hoyland is strong in their presence. John Hoyland carries the modern Turner banner in expressive art. Hoyland is important for today and in the future for those who want to follow the part of the found image. The abstract image that has no reference to anything as an excuse to make a painting. His paintings have its rightful place in the frontline of Art today and will keep its place in the future, as the painter who remained true to himself always, looking for the new, when others were happy with being safe. ‘His work refuses to settle into any kind of academism, refuses to conform to canons of taste or restraint, and is unconstrained by prescriptive definitions of style.’ (John Hoyland:Mel Gooding pg 157).

To take on abstraction and to have to put it out confidently in an age of anxiety for painters, Hoyland plays a big part in carrying the banner for today’s painters, especially so for today’s abstract painters.